| Report Type | Full |

| Peak(s) |

Mount Shuksan - 9,131' |

| Date Posted | 06/30/2024 |

| Modified | 07/05/2024 |

| Date Climbed | 06/20/2024 |

| Author | Ericsheffey |

| Additional Members | NathanP9621, NoahH526 |

| Mount Shuksan via Sulphide Glacier |

|---|

|

"Aw, Shuks"

The Team and Our Goals For a long time now, I've had dreams of developing my skills as an alpine climber to start moving into bigger, more technical terrain. One area that still needs development, and is difficult to train in Colorado, is glacier travel. My primary climbing partner, my brother-in-law Nathan Paxton, also shares similar dreams and limitations. As such, we decided to tackle two more peaks in the Pacific Northwest this year, to hone further our skills in navigating glaciated terrain, and to test ourselves as aspiring alpine climbers. We decided on Mount Baker and it's close neighbor Mount Shuksan as the two peaks we would attempt in this pursuit. We figured out time off from work, put dates on the calendar, and began planning. We decided that for Mount Baker, we would privately hire an IFMGA guide for a 5-day glacier travel seminar to speed up the learning process. Initially, we planned to do Shuksan after Baker, but with the days that we had off from work, and the days that the IFMGA guide could work with us, we pushed our Shuksan trip ahead of Baker. In the months leading up to the trip, I had the opportunity to connect with fellow 14er chaser Noah Hinson (NoahH526 on the dot com) as I helped to introduce him to the world of technical climbing by leading him up a moderate multi-pitch climb near Denver. While climbing, I began learning that his ambitions were much bigger than just climbing the 14ers. He was very eager to learn more about steep snow climbing, rock climbing, glacier travel, and how to utilize these skills to climb big mountains across the world. Although my own knowledge on these topics is limited to a certain extent, I saw a potential opportunity for a climbing partnership with a solid dude that shares similar levels of risk tolerance. Especially since Nathan and I were on the hunt for a 3rd climber to join us on future glaciated objectives, I extended an offer to Noah to join us for Mount Shuksan. We made plans to knock out multiple training sessions with Noah practicing self-rescue, companion rescue, and kiwi coils, and before we knew it, it was time to fly to WA and begin our trek.

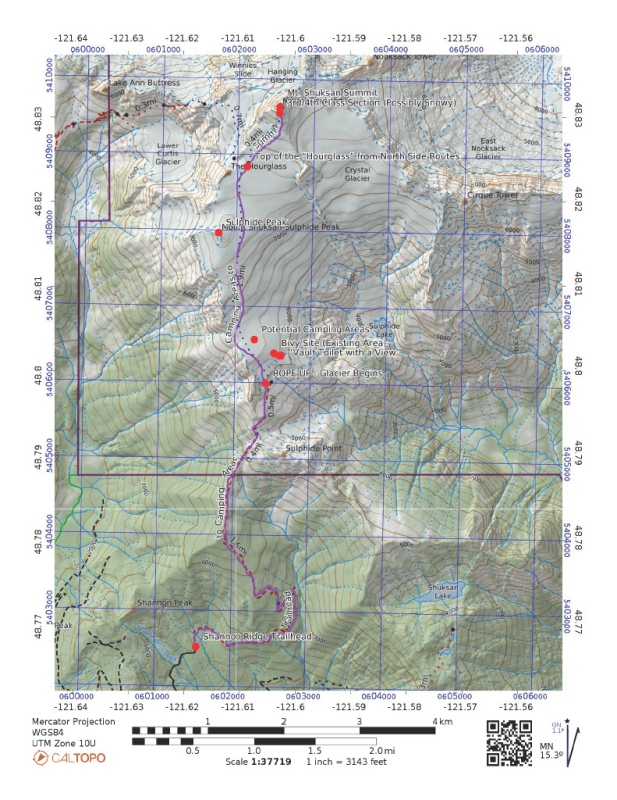

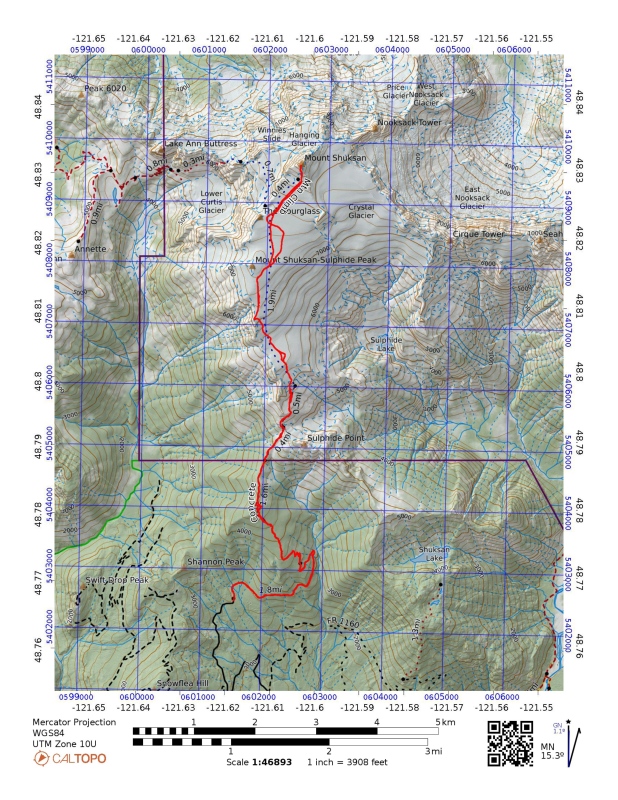

The Start of the Trip As the weeks led up to the trip, we began to solicit beta about the current conditions of the climb. It became increasingly clear that the summit pyramid (which is typically class 3) was still going to be caked with snow and ice, with an additional rime ice difficulty guarding the summit. Although we picked this objective largely just to practice glaciated travel on the Sulphide Glacier, we began packing additional gear to tackle these potentially unusual and out-of-season conditions. We packed a second technical tool for each climber, ice screws, some basic trad gear, and extra cordalettes and slings. We flew together to Seattle, grabbed a rental car, and began driving to our AirBNB in Sedro-Wooley, WA. After a restful night at the AirBNB we took off towards the Shannon Ridge Trailhead where we would begin the hike to high camp. There are typically decent established areas to camp around 6,000' with composting toilets nearby, but the latest beta made it clear the toilets were still under 3+ meters of snow. We decided we would push as far as reasonably possible to allow for quick access to the summit pyramid the following day, aiming to establish a campsite closer to 7,000'+.

We left the trailhead each with backpacks weighing more than 40 lbs, and began the long, slow grind up through the forest. It wasn't long until we began hitting consistent snow, just below 4,200'. Luckily we did not have to put on crampons until much later, only once we were actually on the Sulphide Glacier itself. Overall the approach was fairly quick going, with views continually opening up around us - Mount Baker towering over from one side, and plenty of jagged peaks and glaciers to the other.

Upon traversing around a large rocky outcropping and gaining the Sulphide Glacier, we began to see small cracks in the surrounding snowpack, and larger glaciated terrain in the distance, so we went ahead and donned our technical gear for glacier travel.

When roping up, Noah happily offered to lead us as a rope team and gain experience leading a rope team on actual glaciated terrain. With Nathan and I both having some limited experience doing so on Rainier, and more upcoming glacial travel on Mount Baker, we happily let Noah take the reigns with leading the team across the Sulphide Glacier. We pushed upwards into the late afternoon, and ultimately landed on a flat area of snowy terrain at around 7,100'. We cut a rough platform in the snow and began establishing our campsite. We set up our BD Mission 3P tent, began furiously melting snow to replenish our water and cook our dinner, and cut a bench into the snow in the area of our "kitchen" for us to hang out and eat together as a team.

Our Summit Push We had an early bedtime on our first night out and agreed to be up and moving towards the summit pyramid by 0330 hours the following morning to beat the heat and potential wet slide hazard in the central gully. We were a little slow going in the morning and ultimately left our campsite by 0400 hours instead, with the sun already rising around us as we continued up the Sulphide Glacier. We made quick work of the approach to the summit pyramid, and soon arrived at a small flat area just below the traverse into the central gully. We recognized that the bergschrund in this area was well-covered and decided to unrope as we started the snow climb towards the central gully. Although the snow climbing started fairly low angle, as we continued upwards, it was clear that conditions were quite icy, and that the slope angle steepens quickly. With this objective hazard at play and plenty of technical gear with us, we decided it would be safest to pitch out the majority of this climb, ensuring we all stay connected to each other and the mountain. I also wanted to make sure that all team members felt supported and secure, especially since Noah only had limited exposure to snow climbing before this climb, and no exposure to climbing that necessitated multiple technical tools.

It's worth noting at this point that we had met two additional climbers the day before while on the Sulphide Glacier, two Quebecois-speaking Canadians who also intended to make a summit push this morning. The only problem is that they were expecting a dry rock climb, and lacked quite a bit of technical gear. They each only had one straight shaft piolet and old contact crampons that barely had any front points. Sure enough, they made it to the summit pyramid shortly after us and began to try and follow our line up to the central gully. We recognized that there was a bit of an experience (and expectation) gap between the two of them, and so we offered our assistance fairly quickly, letting them know that I was more than happy to have them tie off more bight knots in our rope and join our rope team. Not only would this keep everyone secured to the mountain in very exposed terrain, but if we continued up as a group, it would limit the risk of rock and ice fall hazards between our team and theirs. They took me up on the offer, and soon enough I was belaying Noah, Nathan, and the two Canadians across to my belay station in the central gully.

I soon took off on the next "pitch" up the central gully. From the belay station I climbed a short section of the underlying class 3 rock that was poking through the snowpack, and then found myself back on hard neve snow, and soon even started hitting 50+ degree sections of ice. There was at least one or two sections that could've taken an ice screw, but I just ran it out past those areas. I ended up running out the 70m rope, clipping draws to occasional tat rap stations poking through the snow along the side of the gully, and built an anchor as far up as I could.

At this point we were getting much closer to the summit, but also beginning to see that we would have to traverse harder skiiers right and up the gully where the top of the mountain was caked with thick rime ice. I brought up my followers, and we began to strategize the next steps. Nathan agreed to take the lead, with hopes that he could make it to the summit on this pitch. Meanwhile, the experience levels and risk tolerance levels between the two Canadians were beginning to become more apparent. One of them unroped and headed straight up to gain the SE ridge with hopes that this would allow him easier access to the summit. Meanwhile his partner Frederic began verbalizing to me that he felt like he was in a bit over his head, and that he planned to now just wait here for us to summit and then begin our descent, and grab him on the way down once we had our rappels set up to go past this section. The one climber continued up the SE ridge and ultimately made the summit on his own terms, but he even admitted afterward that it was "extremely sketchy" and a very bad idea, but that he ended up getting into terrain that he could not downclimb and so he had to just keep pushing. With Frederic still with us, I told him that I thought it would be safer for him to just continue with us as a part of our rope team. Plus, I felt very confident at this point that Nathan and I could safely get the whole team to the summit and back down utilizing our rope skills.

Nathan swapped leads with me and took off traversing to skiiers right and then straight up the middle of the central gully, running out the rope just as he was reaching the rime ice headwall. As Nathan belayed us three up to him, the other Canadian climber appeared on the summit after his perilous icy scramble up the final 100' of the SE ridge. He determined it was best to wait for us to get to the summit to join him so that we could take lead on coordinating the rappel descent. While Nathan belayed us up, he recognized an opportunity to continue to speed things along. Nathan instructed the Canadian climber on the summit to place a mid-clip picket in the snow, pull out the rope that he carried for glacier travel, toss down four bight knots for us all to clip into, and give us a belay up the remaining 15-20 feet of rime ice. This worked like a charm, and before we knew it, we all arrived on the incredibly small summit that was currently entirely covered in snow. Had we not done this, I would've led the headwall and likely placed ice screws to protect it.

Now that we were on the summit, our minds immediately started shifting towards the problem-solving that would occur with the descent. We recognized fairly immediately that there was no option for us all to downclimb back to the gully, so we decided we would rappel off of the summit on a snow picket. Nathan and I got the rappel rigged, connecting our rope with the Canadian's rope for full length raps, and we rigged it on the picket already in the snow placed earlier by the Canadian to belay us up the rime ice. I gave it some hard shock loads to test it, and realized it was not as bomber as I had hoped. Nathan and I agreed to place one of our own pickets behind the first to back it up. It was clear our picket was super bomber right from the start, even with testing it with some shock loads. The plan was for me to rap first to get the ropes down clean, as well as get any additional rap stations established for the group as many tat anchor stations were still covered with snow and ice and inaccessible. We planned for Noah to follow me so that we could double-check his systems, followed by the Canadians, followed by Nathan bringing up the rear, possibly pulling one of the pickets before descending. I took off down the rappel, ultimately finding a small bit of tat poking out of some water ice along the side of the gully that would become our next rappel station. I secured myself, donated two non-lockers to the tat anchor and began tying off the rappel for the safety of the others and to start pre-rigging the next rap.

As I waited for all other four climbers to join me at the tat anchor, I recognized that descending as a group of five was taking too long. Going one at a time with double rope raps was burning valuable time, and we were already starting to see small wet slides and icefall in the areas around us. As the group began arriving to the anchor, I began explaining to everyone that we were going to change up how we conduct our rappels in the name of speed and thus, safety. I prerigged Noah's rappel, backed it up with an overhand on a bight, thus fixing the lines for everyone else. This now allowed us to rappel in pairs, each on a single line, except for the very last person (in this case, Noah). We continued this several times, with myself and Frederic rapping together, Nathan and the other Canadian climber coming down together, and then Noah finally joining us below. The terrain started to mellow, but we knew that we were still in no fall terrain for a while longer, not to mention the open bergschrund that still remained below us. Luckily I only had to build one anchor during our descent, which ended up being two nuts that I hammered into the rock for extra confidence, equalized with a bit of cordelette. This move in particular seemed to really get the stoke going for Frederic who was with me when I built the anchor, as he had never seen trad gear placed before. We continued down, made it past the bergschrund, and ended the raps after 4 sequential ~60m rappels.

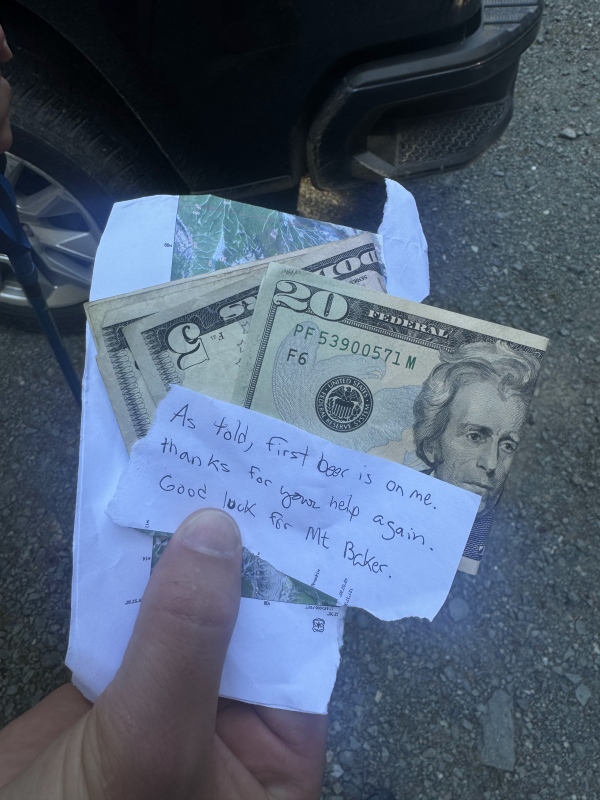

At the base of the rappels, the two Canadians expressed their endless gratitude for our assistance, and promised us multiple times that "the first beer after your trip is on us". We chuckled about that, exchanged contact info, and they continued on their way back down the Sulphide Glacier towards their camp. We followed suit soon thereafter, Noah again leading our rope team down the Sulphide back to our campsite, once again back to a party of three for the first time in several hours.

We arrived back in camp, thrilled to finally rest now that the weight of a successful summit push was no longer on our shoulders. After spending some time replenishing our calories, hydrating, and planning out our exit plan for the following morning, we turned in quite early. It's tough to believe, but that Mission 3P Tent can become quite homely and inviting after a long day out. We ultimately decided that we would leave camp by 0430 hours the next morning to get going back to the trailhead, hoping that an early start would allow for easier travel, and also give Nathan and I more time to rest before heading up Mount Baker the following morning. Day Three We woke up to much colder conditions than expected, and with all our gear getting wet on the summit pyramid the day prior, we woke to find just about everything frozen over, the rope being the most comical. We roped up once more with Noah taking charge leading the rope team across the glacier, crossing several thick snowbridges along the way, and finally getting back to one last snow traverse before hitting treeline where we unroped and ditched all technical gear. From treeline back to the trailhead, we all just put our heads down and pushed, making incredibly great timing back to the trailhead. Little to no photos were taken on descent, other than a few panoramas of the morning alpenglow that I took that can't be uploaded to this TR for some reason. Upon arriving back at the trailhead, we took one more group photo, and then found a note on our windshield. I figured it was going to be a parking ticket since I might not have had the required recreation pass on display (oops), but I was shocked to see it was a note from Frederic, one of the Canadian climbers who climbed the summit pyramid with us. Sure enough, he is a man of his word, and he left us some cash and a note indicating that "first beer is on me". As I told him in an email I sent him afterward, I think this is a huge display of his character as a person and climbing partner. It would be an honor to spend some more time in the mountains with him in the future.

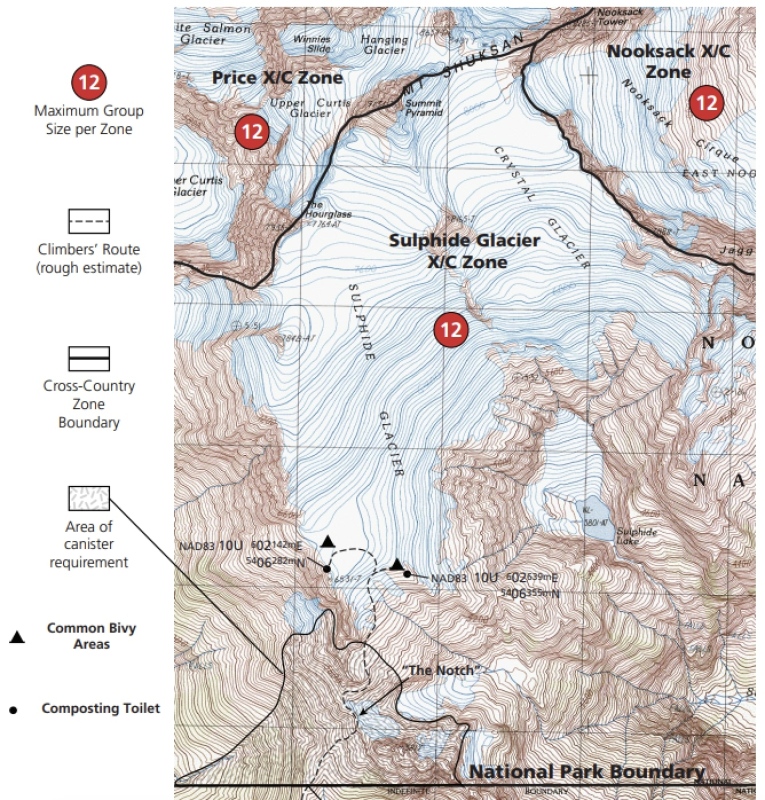

Final Thoughts The glacier travel aspect of this trip ended up being largely one of the simplest parts, but I am stoked that Noah got this introduction to leading a rope team on a glacier. Last year when I led my team up the Emmons Glacier on Rainier, I definitely wished I had worked to get a little more experience beforehand. As far as the summit pyramid is concerned, I know that we weren't the most efficient group to have ever climbed it in those conditions, but I feel good that we used the gear we brought to manage risk and exposure and keep ourselves safe. At no point did I feel like we were in over our heads, and even felt good about keeping Frederic and his partner safe while up there as well. This climb forced us to be a little more creative in new ways, and resulted in our first rappel from a snow anchor, but these are skills that have to be put to the test at some point. Although we started the trip not having spent much time with Noah, I think it's safe to say that after these 2 nights/3 days, we returned to the TH feeling like a tight-knit team of alpine climbers, as if we had all been climbing partners for a much longer period of time. For this, I am most thankful, as I believe we have nailed down a solid team and we can already start planning future trips together. Trip Planning For this trip, we acquired backcountry camping permits from the North Cascades National Park to stay in the Sulphide Glacier X/C Zone (map of zone below). These permits can be reserved beforehand on rec.gov, and then can be remotely issued the day before your climb since the climb starts in a "remote" location. The process was very easy for us, as I just had to have a five-minute phone call with a ranger about leave-no-trace principles, and then the permit was unlocked on rec.gov for me to print on my own. It is very easy to camp outside the area of canister requirement in this zone, which is always nice not having to bring a bear canister.

Thanks for reading! As always, this is simply V1 of this trip report (actually now on V3, but point still stands). As I sort through more photos, remember more details, and so on, I will continue to update this TR for the next few weeks. It's wild just how big the terrain in the North Cascades feels, at much lower elevations than we are used to in CO. For anyone considering it, I highly recommend heading to the PNW to practice and refine your alpine climbing skills. Feel free to ask any questions below or via PM and I will respond as soon as I can. |

| Comments or Questions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caution: The information contained in this report may not be accurate and should not be the only resource used in preparation for your climb. Failure to have the necessary experience, physical conditioning, supplies or equipment can result in injury or death. 14ers.com and the author(s) of this report provide no warranties, either express or implied, that the information provided is accurate or reliable. By using the information provided, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless 14ers.com and the report author(s) with respect to any claims and demands against them, including any attorney fees and expenses. Please read the 14ers.com Safety and Disclaimer pages for more information.

Please respect private property: 14ers.com supports the rights of private landowners to determine how and by whom their land will be used. In Colorado, it is your responsibility to determine if land is private and to obtain the appropriate permission before entering the property.